CONVOY ON 303: THE STORY OF ITS COLLISIONS WITH ICEBERGS, SHIPS, AND AUTHORITY[1]

And how Four Ships hit Icebergs and Twenty-one struck each other

Brian T. Hill

Alan Ruffman, President Geomarine Associates Ltd., Halifax, Nova Scotia

Capt. Stephen L. Sielbeck, (Retired) United States Coast Guard, Commander International Ice Patrol, 2000 – 2003

CONTENTS

Introduction to the Convoy

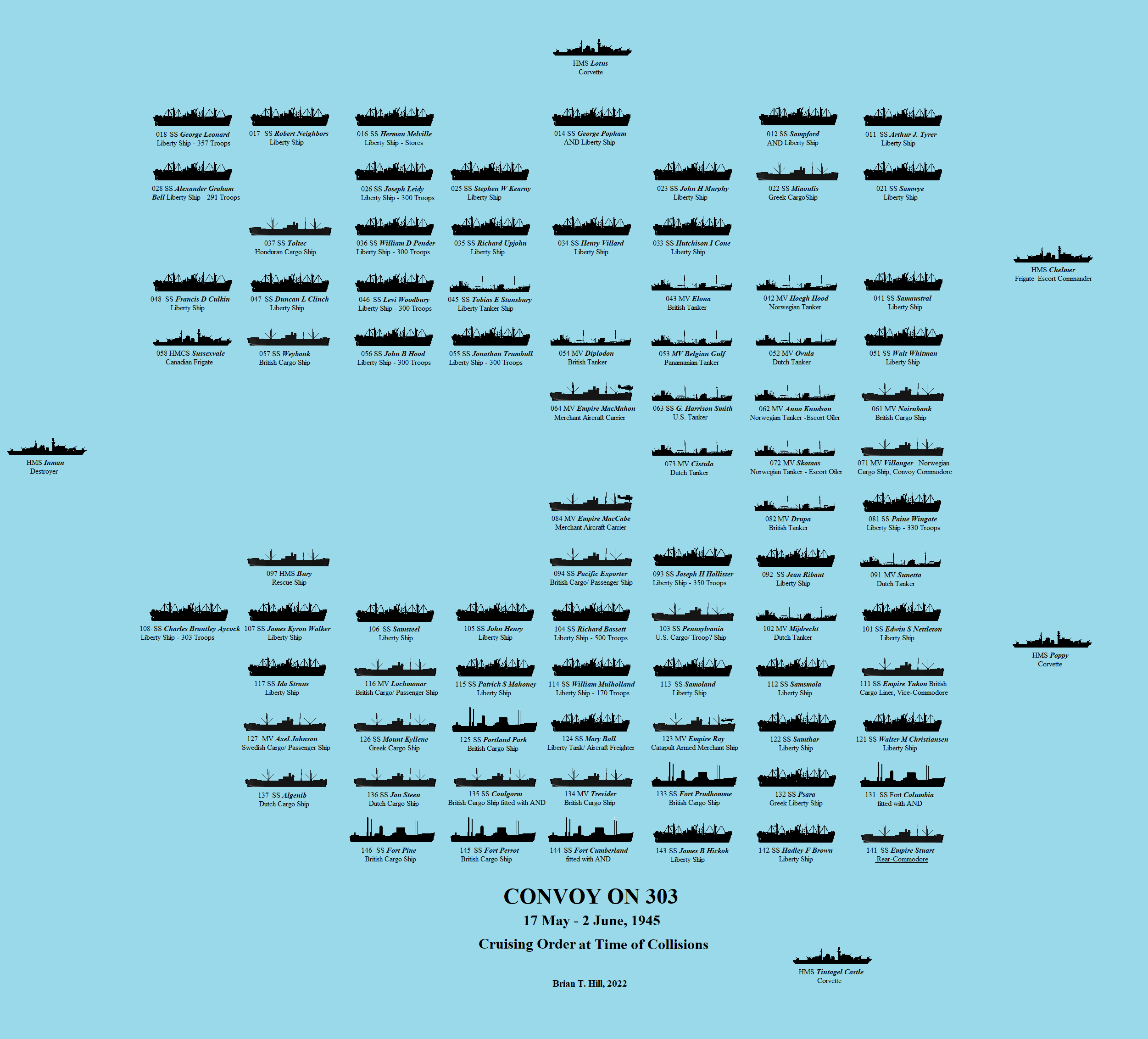

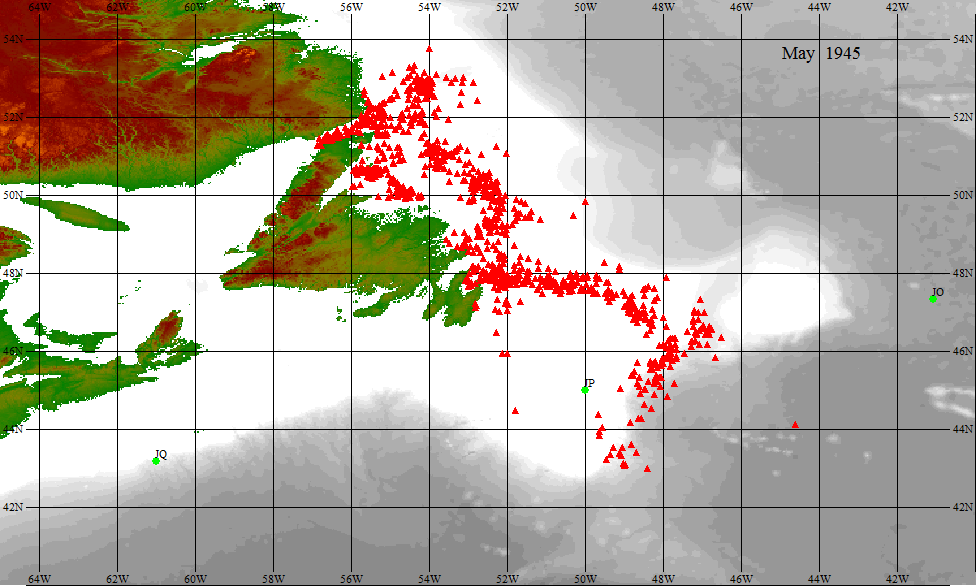

Convoy ON 303 (Figure 1) assembled on 17 May 1945 in the Irish Sea from various ports around its coast. The war in Europe was now over with Germany having surrendered unconditionally on May 7 but Britain was still in a state of war with Japan and there was still some concern that while surrender instructions had been formally issued to the German Navy several submarines, or U-boats, being still at sea, had yet to comply. The convoy was the three-hundred and third coded ON (Outward Bound Northern) for the UK to New York route and was carrying, along with general stores and miscellaneous war equipment, almost 4,000 homeward bound troops. The planned route was straightforward enough following the great circle from the south coast of Ireland to a point off the south coast of Newfoundland. The Grand Banks lay along this course, a notorious place for sea ice and icebergs, and now in spring while the threat of sea ice had diminished the iceberg season had still to peak. With the threat of icebergs looming ahead the convoy was ordered to safely divert which it commenced to do. But then, for some inexplicable reason the convoy turned towards the ice. What went wrong?

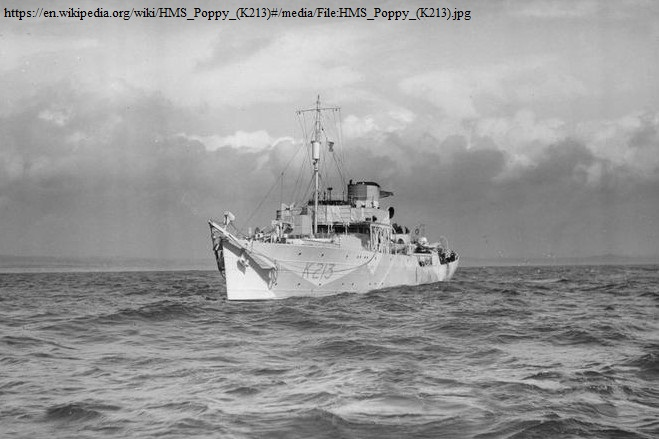

The Command

The naval ships of Mid-Ocean Escort Group B.1 (E.G.B.1) had the task of protecting the convoy during the ocean crossing and had sailed from group headquarters in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, for the various ports of departure: corvette HMS Lotus for Milford Haven in SW Wales; corvettes HMS Poppy and HMS Tintagel Castle for the Clyde on May 16; and the frigates HMS Inman for Belfast and HMS Chelmer for the Clyde on the 17th. Except for the Inman, the last of the destroyers to be acquired from the U.S. under the lend/lease agreement and thus a relatively recent addition, the ships were all battle-hardened from previous convoy duties. The Senior Officer E.G.B.1 (S.O.B.1, or just referred to as the S.O.E.), the Escort Commander, was forty-one year old Commander Rodney Charles Vesey Thomson who had retired from the Royal Navy in 1935 as a Lieutenant Commander but had returned in 1942. In command of the sloop HMS Black Swan the following year he shared the kill of U-124, one of the top-scoring German U-boats of the war, with the corvette HMS Stonecrop thus earning him a DSC and eventual promotion to Commander[2].

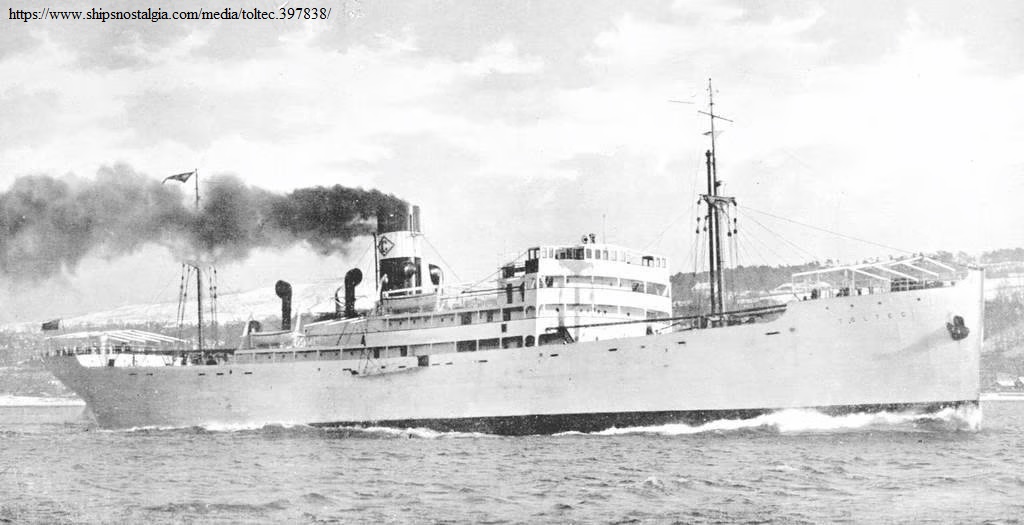

The overall command of the merchant fleet was given to the Convoy Commodore, Capt. S.N. White, Royal Naval Reserve, stationed in the sixteen year old, 4,884 ton Norwegian cargo ship, Villanger. He was a veteran of Atlantic convoys and the accompanying vessel Arabian Prince had also been one of his ships. With a staff of three or four persons comprising his Yeoman of Signals, telegraphist and signalmen, he was responsible for the allocation and formation of the ships within the convoy and the day to day routing and overall performance. Capt. White had served as the Royal Naval Reserve Aide-de-Camp to the King in 1938 and also in 1939[3], the year that war broke out. Once retired, he had returned to active service in spring 1941 and was to serve as Commodore (a civilian position reserved for those with a distinguished Naval or Merchant Navy service) in over twenty North Atlantic runs with several more to the Mediterranean and Freetown[4]. He had seen action on several occasions most notably the east-bound slow convoy SC 52 which on passing east of Newfoundland into almost certain catastrophe had the dubious distinction of being the only wartime convoy to be turned back by U-boats. Four ships were lost to U-boats and a further two went aground as the convoy retreated through the narrow Strait of Belle Isle between Labrador and the northern peninsula of the island of Newfoundland in what Commodore White later described as “his cruise around Newfoundland lasting a week”[5]. Two years later in 1943 and commodore of eastbound SC 122 he again had the dubious distinction of enduring the largest convoy battle of the war in which nine of his ships were lost[6]. While he survived the war with an O.B.E.[7] for his most dedicated service, twenty-one of these highly ranked volunteer commodores did not[8], but for now his unique adventures were not yet quite over.

The Liverpool component of the convoy with the SS Villanger departed at 1600 Greenwich Mean Time (G.M.T., or z) on the 17th along with ships of convoys OS 129 and KMS 104[9] under the escorts of H.M. ships Starwort, Camellia and Columbine and headed west into the Irish Sea. By 0110z next morning, off The Skerries near Anglesey, Wales, the convoy ships rendezvoused with the ships and escorts sailing from the ports to the north. As they proceeded southwards in fog they were met by those coming from Milford Haven in Wales late in the afternoon or early in the evening of the 18th. The combined total of ships now numbered over 100 vessels and steered a course of 245° at eight knots (kt) paralleling the SE coast of Ireland until 0300z in the early morning of the 19th when Convoy OS 129/KMS 104 and their escorts detached, the former for Freetown, West Africa, while the latter would split off and head through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean. Now on a more southerly course of 223° almost due south of Cobh, Ireland, the convoy was joined by the frigates H.M. ships Loch Shin, Cotton and Antigua of the local Escort Group 19 (E.G.19) which had the responsibility of convoy protection in the home waters of the Irish Sea and western approaches[10]. Additional protection was also provided by the anti-submarine warfare trawlers/whalers H.M. ships Huddersfield Town, Southern Spray and Vatersay[11]. The potential threat from rogue U-boats was taken very seriously and for the remainder of the day air cover was supplied by Royal Air Force Coastal Command anti-submarine Vickers Wellingtons and Warwicks. Convoy routing around the south coast of Ireland and thence straight across the Atlantic had only been in effect since September 1944 when the long-range threat of enemy submarines and aircraft from occupied France had been removed, the routing previously being through the North Channel to the north of the island. U-boat attacks in home waters from bases in Germany still continued, however.

The convoy continued on the course of 223° until the early evening of the 19th when it met up with some thirty-six ships of the Channel component of the convoy with ships from south-east and southern England escorted by the destroyer HMS Vesper, the corvette HMS Clematis and the Free French corvette Aconit in position 49°58´N, 10°04´W. The S.O.E.’s report gives a time and date of 1200 on the 19th. It is not clear whether G.M.T. or British Summer Time (B.S.T.) is meant. Most of the times given in the report are denoted with a B presumably standing for B.S.T. which during the war years was G.M.T. plus 2 hours. In this instance, neither 1200 in G.M.T. or B.S.T. agrees well in comparison with other known times and positions but a time of 1600z is consistent with the computed and stated average speed of eight knots of the convoy at this time and is believed to be what was meant. Likely at this time the convoy then altered course to a more westerly track for the great circle route across the ocean

At 0651z on May 20th HMS Vesper stationed on the front port side of the convoy reported seeing the possible schnorkel of a U-boat and commenced an attack with a pattern of depth charges in the approximate location of 50°10´N 13°08´W, some 140 nautical miles (nm) to the SW of Ireland. The convoy took evasive action by a ninety degree turn to starboard. It was considered likely that what had been seen was little more than smoke left over by a marker flare dropped from an aircraft deployed by one of the accompanying merchant aircraft carriers (MAC ship). The convoy resumed its original course but E.G. 19 kept vigilance over the area for the next hour and a half and at 1600z the ships, Loch Shin, Cotton and Antigua departed. At noon G.M.T. next day, the 21st, the remaining British Home Water Area escort group ships, Vesper, Clematis and Aconit, left ON 303 to escort the incoming convoy HX 355 from Halifax, Nova Scotia. The westbound convoy was now solely in the hands of S.O.E. Thomson’s five ships of Mid-Ocean Escort Group B.1.

The Route

From almost the beginning of U.S. involvement in the war their navy’s Convoy Routing & Planning Section had assumed control of convoy operations in the Western Atlantic which in the North Atlantic was basically west of 26°W. While retaining strategic authority with the U.S., the Washington Atlantic Convoy Conference of spring 1943 transferred full convoy operations to the British and Canadians for all North Atlantic convoys, essentially those operating between New York and Liverpool. The British had control from their home waters to 47°W on the Grand Banks while west of this line lay under the operational control of the Canadians in the newly authorized command of Commander in Chief of the Canadian North-west Atlantic (C. in C. C.N.A.). E.G.B.1[12] would thus continue to rendezvous with the Royal Canadian Navy (R.C.N.) at a point on the Grand Banks west of 47°W referred to as WESTOMP, or Western Ocean Meeting Place. The R.C.N. would then take over the convoy and escort it for the rest of their voyage leaving the Mid-Ocean Escort Group to refuel at St. John’s, Newfoundland, in readiness as escort for the next eastbound convoy back across the Atlantic.

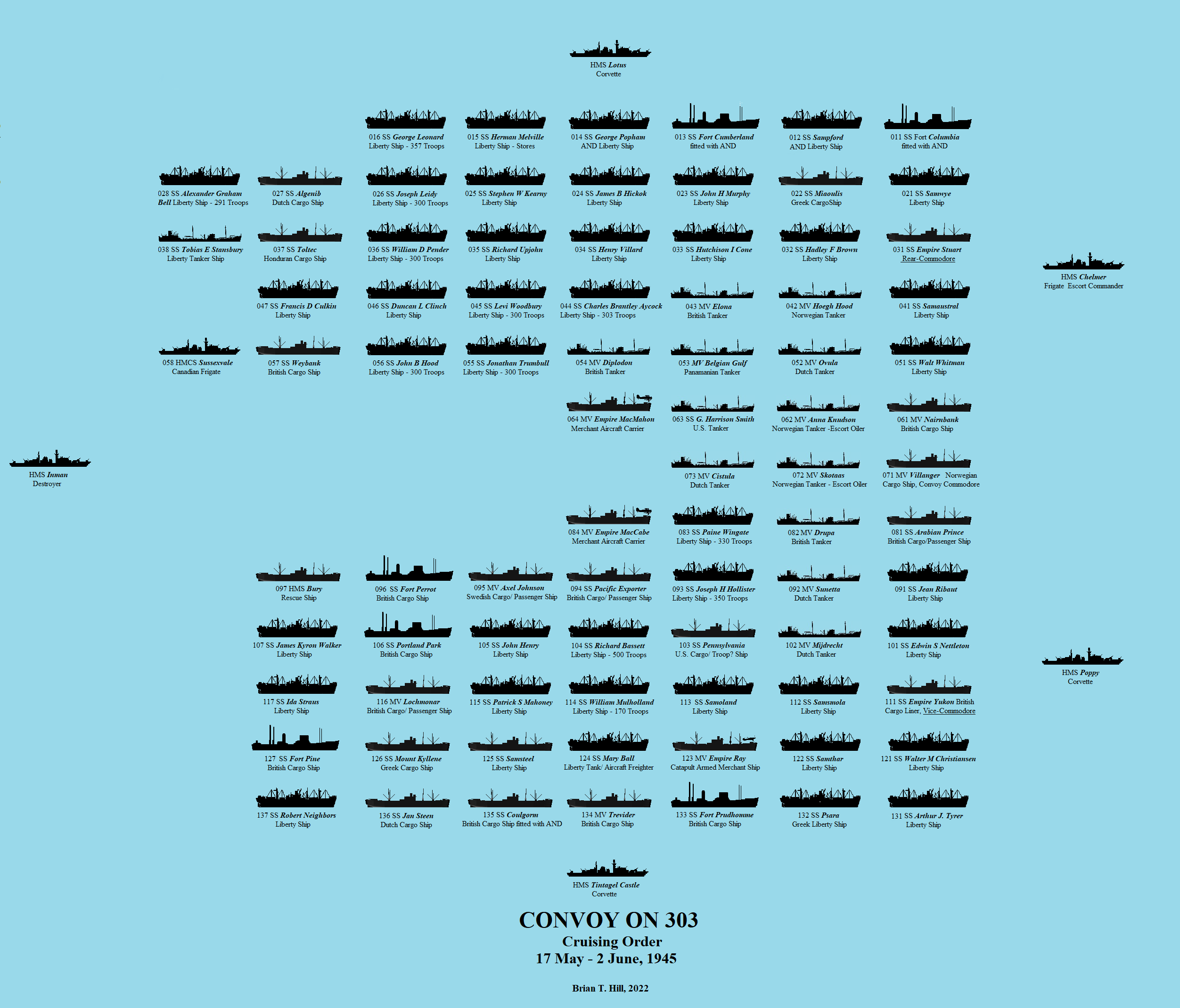

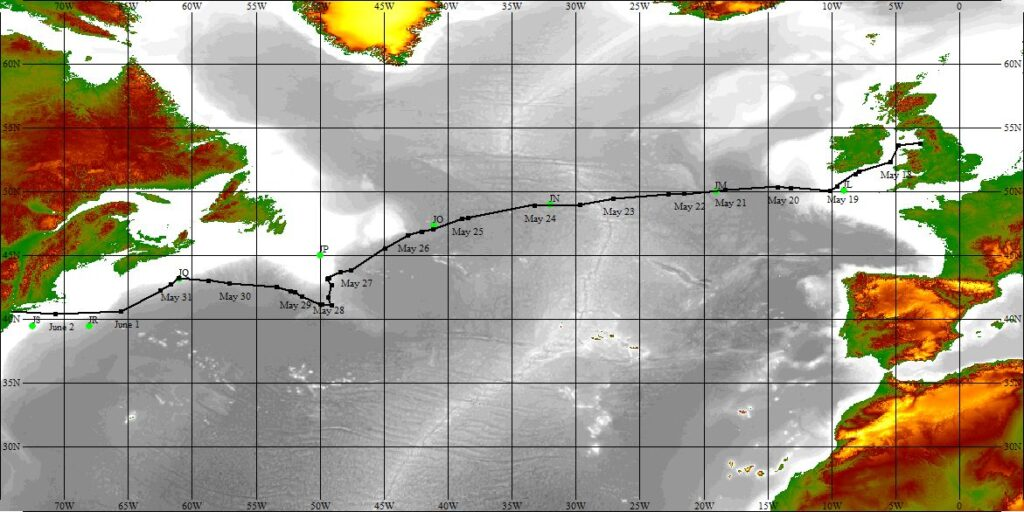

The Convoy Commodore’s report includes the daily 1200z positions from May 18 to June 2 as well as an untitled chart of the North Atlantic showing the intended route for the convoy with waypoints marked sequentially JL through JS (Figure 2[13]), JL being to the south of the southwesterly point of Ireland and JS in the approaches to New York. The points JL to JP on the Grand Banks outline a gentle curve across the central North Atlantic which suggests the Great Circle route. The subsequent points JQ to JR to JS are the straight rhumb lines to New York. Neither Commodore White nor S.O.E. Thomson mention an original WESTOMP position and during the course of events it appears to have been changed at least once to meet changing situations. At the outset of the voyage one might expect that it lay somewhere along the course outlined by the J points probably in the area just west of JP.

From WESTOMP the convoy was to proceed to its main destination New York but at various points, even preceding the WESTOMP, ships were to be detached to various locations such as Curacao, Newfoundland, Quebec, Halifax and Boston.

The Ships

The convoy was screened by the Ocean Escort with Chelmer and Poppy ahead of the convoy, Tintagel Castle on the starboard beam, Inman on the port side and Lotus bringing up the rear. It was a large convoy with eighty-three merchant ships the bulk of which were the American built Liberty ships. The convoy was distributed in fourteen columns with up to eight ships in line ahead. The spacing for this convoy was not specified but was typically up to a thousand yards between columns and five or six hundred yards between ships in the line. Thus a convoy like this could be up to thirteen thousand yards wide and over four thousand yards long covering an area of almost eighteen square miles of ocean. A simple diagram of a convoy with the ship allocations was called a Convoy A1 form with the columns numbered from left to right and the ships in the column numbered with the head of each column being one; thus the Convoy Commodore, typically at the head of the convoy, was in the case of ON 303 in the Villanger in position (pennant number) 71 being the first ship in the seventh column, half way across the front. In case things went wrong and for some reason the Commodore’s ship was incapacitated his duties fell on an appointed Vice-Commodore which in this instance was the master of the Empire Yukon in position 111, the first ship in the 11th column, four columns to the right of the Commodore. In case things went really wrong a Rear-Commodore was appointed and this was the master of the Empire Stuart leading the outermost starboard column in position 141. Both the Vice-Commodore’s and Rear-Commodore carried three signalmen each for this eventuality.

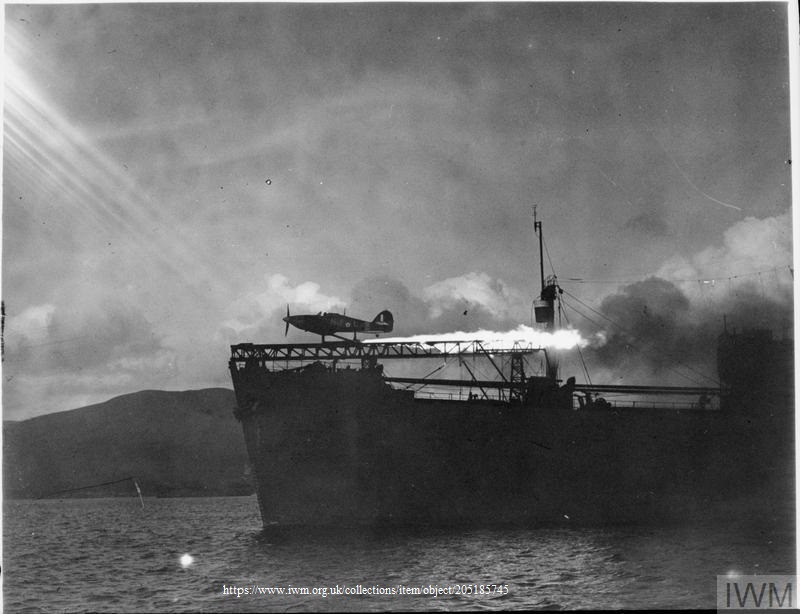

Typically, all the merchant ships in the convoy carried defensive light armaments but for Convoy ON 303 there were three other heavily armed escorts in the ships in line. These were the Merchant Aircraft Carriers (MAC ships): the Empire MacMahon and the Empire MacCabe, and the Catapult Aircraft Merchant (CAM) ship, the Empire Ray, to be found in positions 64, 84 and 123 respectively. Both the MAC ships were converted tankers with the capability of carrying four Fairey Swordfish aircraft each. That these were biplanes seems at odds with an era which had just seen the first jet aircraft combat but, in fact, they were remarkable aircraft for the job. The large surfaces of the two wings provided the lift required for take-off and landings from the short decks at low speeds and the plane could carry a wide variety of weaponry either mines, bombs, rockets or a 1,670 lb (760 kg) torpedo. The Swordfish achieved fame with its crippling of the German battleship Bismarck and over its wartime career was responsible in the sinking of eighteen U-boats from ship carriers[14]. While the role of the MAC ship may have been exaggerated in extending a veil of invincibility around the convoy its presence within was still highly regarded and most welcomed by the fellow mariners[15].

The pilots of the modified Hawker Hurricanes of the CAM ships were not as fortunate as their Swordfish counterparts as the rocket propelled catapult launching system initiated a one way trip. If the pilot could not make it to dry land then his only alternative was to ditch, or parachute, close to a ship and hope for a successful pickup. The system was used nine times for the loss of eight enemy aircraft[16]. Although modified for the launching system CAM ships continued to carry their normal cargos. Often, their position within the convoy was at the head of one of the outboard columns so they could readily maneuver into the wind to assist the take-off but here it is noted that the Empire Ray was positioned three columns in on the starboard side and the third ship in line in position 123. The two MAC ships were placed in the center and the other tankers were generally in the center portion also. Several ships were fitted with the Admiralty Net Defense Net, known as AND. These were steel nets suspended from the ship’s arms around most part of the hull to fend off torpedoes. Ships so fitted were normally allocated to the exposed outer columns. Stationed at the rear of the convoy in position 97 where it could respond quickly to a developing situation was the Rescue Ship Bury, a converted passenger-cargo vessel of 1,686 tons. Refitted with all the devices and aids for getting shipwrecked sailors onboard quickly and operating rooms for treating the wounded these ships were a great morale booster.

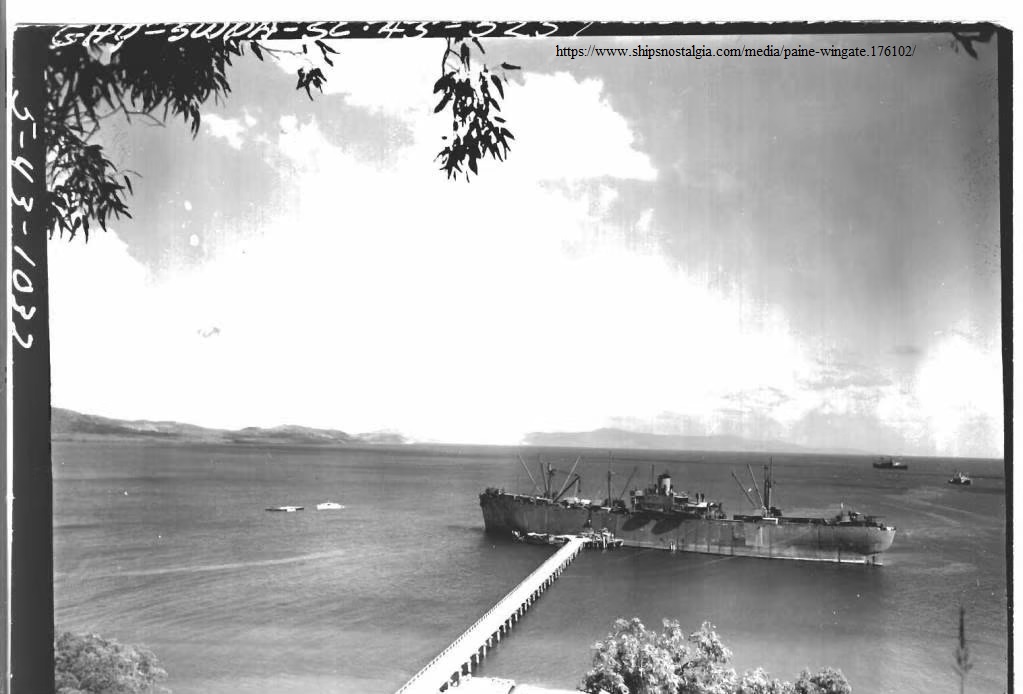

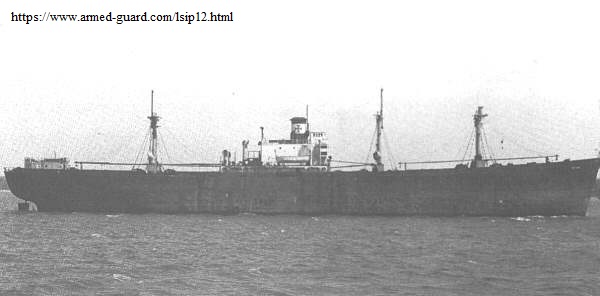

The greatest portion of the convoy were U.S. Liberty cargo ships, a relatively cheap and easily mass produced 441 foot long vessel ordered by Britain to replace the growing tonnage of losses by U-boats and other enemy action but most remained as part of the U.S fleet. Some were modified as troop carriers of which there were at least twelve in the convoy carrying some 3,798 troops. The tradition was that all the American Liberty ships were named after prominent though deceased Americans, perhaps now not so many well-known as back then. U.S. Liberty ships transferred to the British fleet were all named beginning with “Sam”, not as some suppose as a connection to the U.S. “Uncle Sam” but as an abbreviation for ‘Superstructure aft of mid-ships”. Liberty style ships built in Canada were named Park ships, i.e. SS Portland Park. Similar style ships also built in Canada for the U.S. and transferred to Britain under the lend/lease agreement were the “Fort” ships, i.e. Fort Prudhomme, Fort Pine, etc. British merchant ships owned by the British Government were named “Empire” and included the MAC and CAM ships while others were present also. In addition to the homeward bound troops there were 205 passengers accommodated in four ships for a total of 4,003 persons above and beyond the normal ships’ officers and crew, a compliment of perhaps another 4,000 people. The ships transporting all these persons were allocated positions within the main body of the convoy (Fig.1).

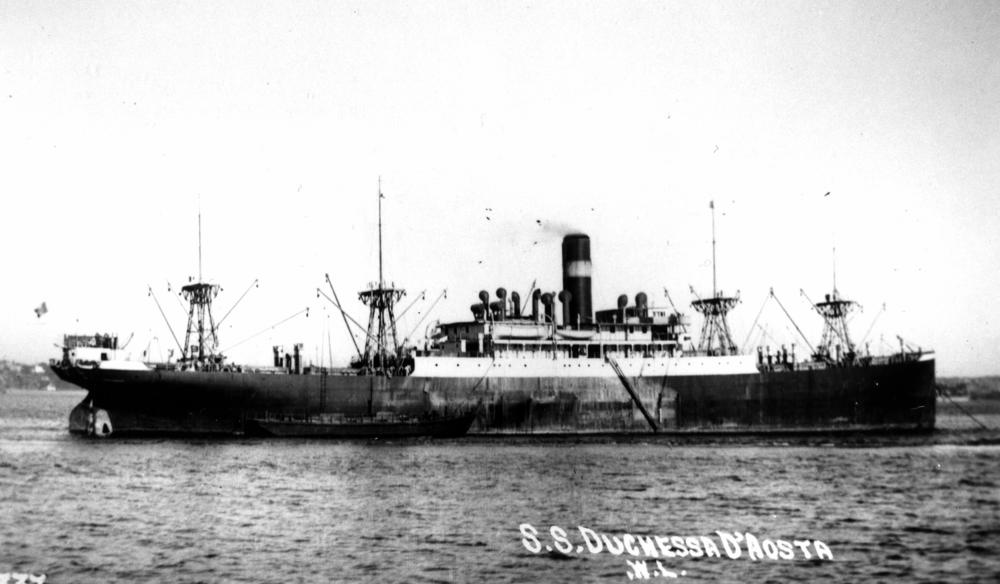

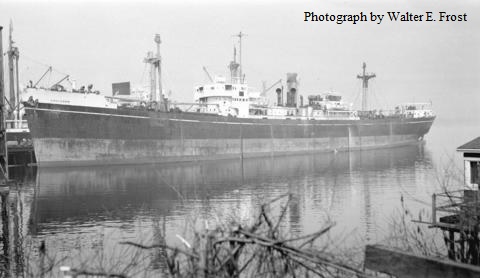

In all, there were thirty-six U.S. cargo and troop ships, one U.S. tanker, twenty-four British cargo ships, five British tankers, eight cargo ships of other nationalities, eight tankers of other nationalities, and one HM Canadian Ship, Sussexvale, returning for conversion to Pacific duties. Including the five escorts the convoy amounted to eight-eight ships. A brief description of each of the ships, with photographs if available, is included to illustrate the main text of this article or is given in the Appendix. The history of the Empire Yukon (the Vice-Commodore’s ship) is worth noting and of more relevance to this narrative is the Liberty Ship Ida Straus. It was built by the Todd Houston Ship Building Corporation, Texas, and launched on 10 August 1944. It was named after the wife of Isidor Straus, a prominent New York business man and politician. Having spent the winter of 1912 in Europe the Straus couple sailed for New York on the RMS Titanic when on the night of April 14 it struck an iceberg and started to sink. Being urged by the ship’s officers to take to the lifeboats she refused to leave her husband. They and approximately 1500 others died as the ship went down. His body was recovered a few days later but hers was never seen again. Their love and commitment to each other inspired the naming of memorials, a park, a school and a ship. Thirty-three years later there was to be another remarkable twist of fate.

The Ice

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

The_Royal_Navy_during_the_Second_World_War_A17353.jpg

Fog, and the floating hazards of ice and, in the days of sailing ships, derelict hulls and wreckage have long been the bane of sailors in the western North Atlantic. Ice takes the form of sea ice or icebergs and has separate origins. Sea ice is formed from the freezing of sea water principally from the Arctic and sub-Arctic waters to the north drifting down with the Labrador Current as the winter season progresses. As air temperatures fall ice is also formed along the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland mixing with the ice drifting from the north and in a typical year will reach a maximum extent stretching south of St. John’s and over the Grand Banks. Ice also forms in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in severe years this can extend along the south coast of Newfoundland to meet up with east coast ice so that the whole island may be surrounded. In some years, however, the sea ice may be limited to the waters off the north and northeast coast. By May sea ice has normally receded to the north end of the island and according to the ice patrol no sea ice of any consequence remained south of 48°N by 11 May 1945 or south of the Strait of Belle Isle at the north end of the island by the end of the month.

The other form of ice is icebergs, calved principally from the large glaciers of western Greenland although a few also come from the Canadian Arctic islands opposite Greenland. Some ultimately drift upwards of a thousand miles or more to the Grand Banks melting and sometimes fracturing into smaller bergs as they go. Bergs are categorized into various sizes ranging from bergy bits, the size of a car that may be awash, up to very large, the size of a city block. Even more extensive are ice islands, calved from ice shelves or where because of topography the glacier has been able to flow considerable distances out over the sea spreading and thinning in the process so that as pieces detach they may be many square kilometers in area but are often little more than about 15 meters high. Most icebergs melt away completely but some will inevitably drift southwards relatively intact to the Grand Banks on a journey that may take up to three years sometimes grounding along the coastline of Baffin Island or Labrador and perhaps being locked up in a fiord for a winter or two. The presence of sea ice around the icebergs helps protect them from wave erosion so that in a year where sea ice is extensive one can generally expect a large number of icebergs drifting further south than usual. When they drift southwards of Newfoundland in about latitude 48°N they pose a threat to the traditional trans-Atlantic shipping routes for entry into Canada, or the northeastern seaboard ports of the U.S such as Boston, New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Reported in the St. John’s Daily News Wednesday June 6, 1945, p.3 col.5 bottom, as having struck an iceberg: Hits Iceberg.

Montreal. June 5 – (Reuter’s) – The British merchant ship “Empire Yukon”, 4,000 tons, of London, is arriving here with her bow smashed above the waterline with an iceberg off Newfoundland. She will be beached here near Vickers shipyards and repaired there.

Photo source: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Empire_ships_(U%E2%80%93Z)

The presence of icebergs in the trans-Atlantic routes had long been a concern. Hundreds of ships had been damaged in encounters with them over the years, some being totally lost often with many lives[17]. Many other ships had simply disappeared with icebergs being considered the most likely culprit. Even in the decades before the notorious sinking of the RMS Titanic as ships became bigger and faster iceberg sightings were often reported in a variety of newspapers and shipping journals and subsequently in bulletins of the U.S. Hydrographic Office. There were calls for some kind of government patrol service for the observation of icebergs and destruction of derelict vessels but it was not until the tragedy of the Titanic that such a service was recognized as justifiable and the International Ice Patrol (IIP) under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Coast Guard was inaugurated two years later in 1914 and continues to this day. Its mandate is basically to observe, monitor and warn of any icebergs drifting south of 48°N into the shipping lanes. The number of icebergs entering this area is highly variable from one year to the next and can vary from zero to the thousands. The iceberg season normally peaks in May or June with, according to the IIP, an average of 474 bergs crossing south of 48°N in a season.

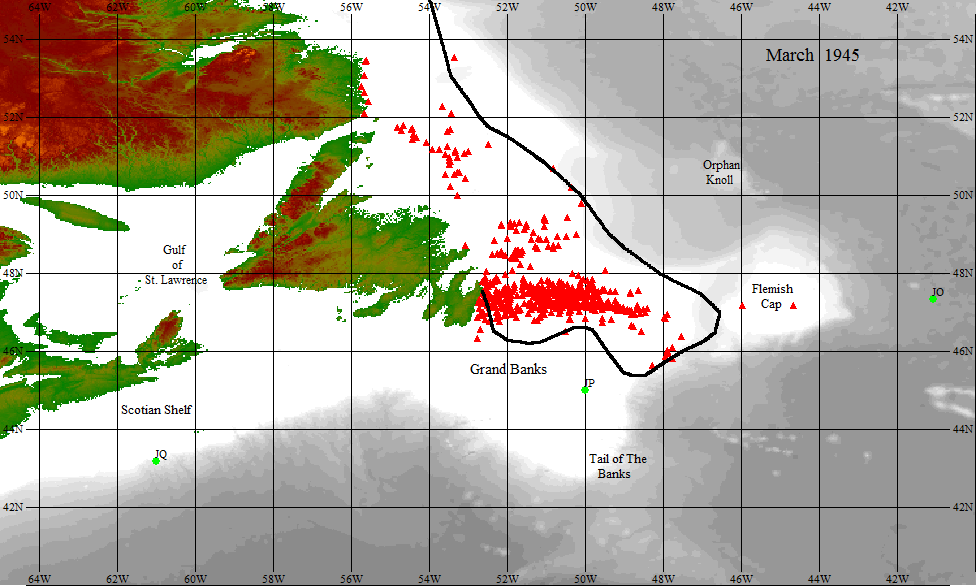

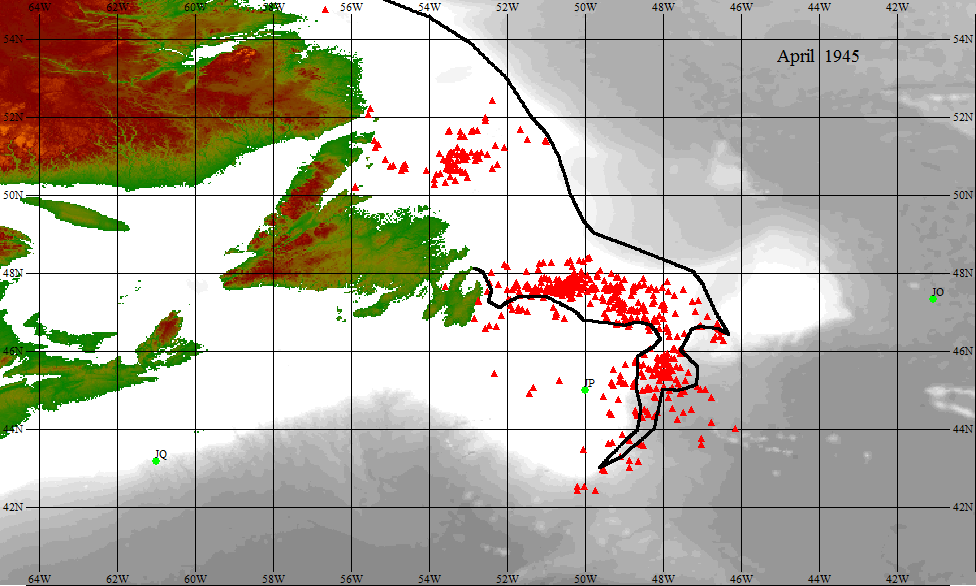

During the war years 1942 – 1945 the IIP services were suspended but ice conditions were continued to be monitored for naval purposes and the observations were eventually published in the IIP Bulletins once the war had ended. Sea ice conditions in 1945 were, in fact, close to average with a maximum being reached and extending over the Grand Banks in April but by May the extent had shrunk to off the northern part of the Island of Newfoundland. Icebergs, on the other hand, were numerous with 1087 passing south of 48°N during the iceberg season with 253 passing south in April alone and a further 256 in May. Thus, April and May provided essentially half of the year’s total. Icebergs melt as they drift, the rate of deterioration depending on several factors such as size, shape, amount of protection by sea ice, sea state, wind speed, and air and sea temperatures. The most southerly observed during this time was on the April 27 in the vicinity of 42°25´ N, 50°00´ W, almost 400 miles since crossing 48°N. During June, icebergs drifted further south than this.

Icebergs had been reported as far south as 43°N in early May but observations had been limited by bad weather for at least a week prior to the transit by Convoy ON 303 as noted by the Hydrographic Bulletin of the U.S. Hydrographic Office. It would seem reasonably safe to assume from the ice reports from late April onwards that icebergs could be expected as far as 43°N if not further south. All these ice and iceberg data were available to the convoy route planners within the British, American and Canadian navies in 1945.

The Collisions

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Mackworth_fog_buoy,_Merseyside_Maritime_Museum.jpg

The average speed of the convoy from noon G.M.T. on the May 19 to 20 was 7.5 kt, down slightly from its previous eight knots but this could have been due to the diversion on seeing a possible U-boat. However, over the next 24 hours till noon on the 21st the speed was reduced again to 6.5 kt and even slower again till noon on the 22nd at 5.3 kt. The records do not indicate whether zig-zagging was in effect but this was confirmed by an ex-Midshipman of the Empire Stuart for the early part of the voyage. This, as well as the generally adverse conditions which were known to have plagued the convoy during the whole passage was the likely cause for the loss of speed over ground. Fog with zero visibility is mentioned as being almost continuous for four days after the 23rd although by this time the convoy was making good progress. No doubt fog buoys were deployed, devices designed to throw out a rooster tail of water when towed behind a vessel allowing the ship astern to maintain close visual contact. To aid in keeping contact with these at night these were sometimes enhanced with a small blue light, as were the stern of the vessels, and first-hand accounts make no issue of the stress of the look-outs and officers of the watch keeping these small lights in view. From noon on the 22nd till noon on the 23rd the speed had increased to 9.1 kt. Later that evening the British freighter, Arabian Prince, and the Dutch tanker, Cistula, took leave of the convoy for Trinidad and Curacao respectively.

For the next twenty-four hours until noon on the 24th the average speed had increased again to 10.1 kt. Instructions were then received from the Admiralty that the British tanker, Drupa, was also to go to Curacao and it was detached at 1100z on the 25th in 47°52´N 38°09´W, the convoy being now a little more than half way across the Atlantic to its destination; the convoy was now down to 80 ships. The 24 hour average speed till noon was 9.9 kt and for the following 24 hours till noon on May 26th was 7.9 kt. As the convoy crossed the Atlantic along the Great Circle the course had slowly decreased from 269°, almost true west, to a more west-southwesterly course of 246°. Although not exactly on the J points outlined on the chart or the calculated Great Circle to point JP it was still generally along that track to within a distance of thirty or so miles as in Figure 2.

Source: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Fort_ship

On May 17, the same day as Convoy ON 303 was gathering sail, westbound Convoy ON 301 had been negotiating thick fog on the Grand Banks when the Dutch freighter SS Aalsum slammed into an iceberg damaging the bows with subsequent flooding of the forepeak. The location was in 45°N 48°W essentially on ON 303’s track to point JP. Two days before, the Senior Officer H.M.C.S. Eastview of Convoy ON 301, with the probability of encountering ice, had nightly stationed one of his escort vessels, H.M.C.S. Lambert, seven miles ahead on “ice patrol”. At dawn on the 17th with visibility down to about a quarter of a mile the Lambert reported an iceberg ahead. Sound signaling was made to initiate evasive course alterations to port but not all ships heard the signals. There was general confusion but only the one ship hit an iceberg of which there were several; “A very uneasy quarter an hour was spent by all concerned until escort astern reported bergs were clear”[18].

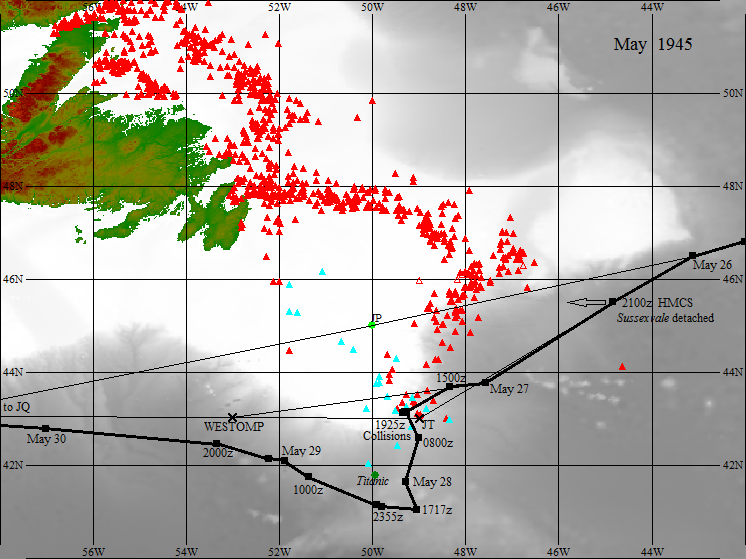

On May 25th, with ON 303 nearing the Grand Banks, the C. in C. C.N.A. sent a signal to the convoy escort and the various levels of high level command including the Admiralty, and the Commander of 10th Fleet Convoy and Routing, with orders for the convoy to head for a new position, JT, at 43°N 49°W once it had crossed 42°W on its current track, thence to position JQ omitting JP in the centre of the Grand Banks along which route would likely have been the original WESTOMP. This was then a diversion southwards and although the orders give no reason it can be reasonably assumed this was to avoid the known icebergs extending like a barrier along the eastern edge of the Banks and extending this far south. While the signal was sent from the Admiral in Halifax it is likely that it was initiated from the British Admiralty’s routing division as suggested by later evidence and also by agreement this area of the Atlantic was under British authority. The convoy would have crossed 42°W about midnight local time and it appears to have waited until morning light before making the turn to a southwesterly course either at or slightly before noon GMT, there being a three hour difference with local time. The noon position indicates that the convoy was still close to the originally planned route.

The first information we have on a new WESTOMP is in a signal from the Flag Officer Newfoundland, or FONF, (the RCN Commanding Officer in St. John’s) sent 2024z, May 26th, to the convoy informing that his Western Local Escort Group 8 comprising of HMC Ships Kenogami (senior officer), New Liskeard, Forest Hill and Drummondville would depart 1000 next day for WESTOMP in 43°02ʹN 53°01ʹW at 1300z on the 28th. With routing through point JP now cancelled the diversion lay southwestwards to point JT thence almost due west to point JQ with the WESTOMP position directly on the track JT to JQ.

Many signals had gone back and forth between the convoy and headquarters regarding destinations of various ships and on the afternoon of the 26th orders came through for the H.M.C.S. Sussexvale, which had joined the convoy at the last minute, to detach and proceed independently to Halifax where she was to be re-fitted for tropical conditions in warfare against the Japanese. This she did a short time before 2100z on the 26th, likely at about the same time the signal arrived with the new WESTOMP, in the approximate position of 45°30ʹN, 44°50ʹW and her signal to Admiralty confirming her detachment gives both the Sussexvale’s and convoy’s positions courses and speeds and indicates that at that time they were still very close. The convoy, now seventy-nine ships, was at a steady speed of 10 knots on a course of 233° which on backtracking reveals that it began its diversion earlier in the day around noon. The Sussexvale, assuming a more westerly course of 265°, now had to battle her way through the phalanx of icebergs guarding the eastern edge of the Banks. This course put her crossing the eastern edge of the Banks at approximately the same location as Convoy ON 301 and as Convoy ON 303 was originally routed. Later, in the evening of the 27th, she sent a signal to Halifax with her estimated time of arrival and that her underwater ASDIC fittings had been damaged [presumably by ice].

In fact, since noon on the 26th till 2100z when Sussexvale detached, the convoy had achieved an average speed of 10.4 kt, her best so far on its voyage when the overall average speed from noon on the 22th after reaching the open ocean and achieving reasonable speed to noon on the 26th was just over 9.5 kt. In order to reach WESTOMP for 1300z on the 28th, a distance of 410 nm, the convoy was now expected to maintain an average speed of 10.25 kt, rather ambitious given its prior performance.

Although the International Ice Patrol was suspended until 1946 ice observation was still carried out by Task Group 24.7, Ice Information Detachment, and on 27 May at 0130z a naval message was issued by the commander of the group to “All commands concerned with Nfld and St. Lawrence ice bulletin north of 40 degrees north and west of 35 degrees west.”, stating:

Ice Bulletin 26 May. Newfoundland Area. Reported this date Icebergs at 45 58 N 47 29 W. 45 58 49 00. 46 06 48 04. 46 00 48 11 Two at 46 18 46 46. Singee [sic=single] 25th 47 45 52 55. Except others wildy scattered throughout Grand Banks area from coast to 46 00 W and south past 44 00 N. Numbers continuing to move past 44 40 N near 100 fathom curve along eastern edge banks also within 50 miles of coast past 47 45 N. Main pack estimated north of 49 50 N and west of 52 00 W with ice to beach in places from Notre Dame Bay north past Strait of Belle Isle. 27 0130/5/45

Essentially, this was a warning given the southward drift of the current that bergs were directly in the original path of the convoy. Although a copy is attached to the S.O.E.’s report neither he nor the Convoy Commodore mention receipt of this bulletin, nor indeed, did they mention any diversion for JT. The 2024z, May 26 signal from FONF mentioned previously giving the new WESTOMP also continues, “Attention is drawn to CTG 24.7 daily ice bulletin”, which implies that the Ice Bulletin of 26 May quoted above, although time stamped here at 0130z on the 27th, had already been sent earlier on the 26th.

In the morning of the 27th, the fog which had plagued the convoy for the past few days eased up which allowed the convoy to tighten up and the ships bound for ports in Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence maneuvered in to the starboard wing columns. The Commodore’s Convoy A1 form shows the disposition of the ships at this time and is represented in Figure 3. The convoy website[19] of naval historian Arnold Hague, RN, RNR, also gives the position of each of the ships which was evidently the allocation before the repositioning of the ships on the 27th. It shows the positions of the 081 Arabian Prince and the 073 Cistula before they were detached on the 23rd as well as all the other original allocations of the ships.

By noon on the 27th the convoy was still on a southwesterly track of approximately 230° aiming for the newly designated JT position of 43°N 49°W which would essentially clear all known bergs. However, the 1500z position was almost due west of the position at noon. There is nothing in the records to suggest why the change of course (apparently to 270° for a three hour period) but now instead of rounding the bergs at the Tail of the Grand Banks the convoy was heading straight towards the bergs scattered along its eastern edge. Not only that, but the course given at 1500z was back to southwesterly 233° putting the convoy at even more risk as instead of crossing the area of bergs perpendicularly, the shortest way through, it was now angled along the edge of the Banks the longest way through them and the three hours of westerly steaming had now put the convoy into their midst.

At 1902z in 43°08´N 49°18´W at 9.5 kt in thick fog HMS Chelmer in the lead obtained a radar contact at 241° range 6000 yards which was initially believed to be a surface craft. A number of other confused echoes were also reported and while investigating, at 1915z, they found themselves under an enormous iceberg the full length of which could not be seen but was estimated at ¾ mile. There was also another berg to the northward and growlers (small icebergs about the size of a house). The larger berg was later estimated at 4,500 feet long by 3,300 feet wide and 50 feet high (1.4 km x 1 km x 15 m). Rapidly sizing up the situation S.O.E. Thomson realized that collisions were inevitable and either the convoy would hit the iceberg at 9.5 kt or must turn ninety degrees together in which case a number of ships would likely collide with each other. He, therefore, asked the Commodore to do a “ ‘Double Item’ turn (ninety degrees to port together)”. In the words of Commodore White:

“As indications were that the ice was very close it was necessary to have no delay in turning but my first 15 second blast not being repeated I made a second 15 second blast which seemed to wake every one up and produce good response. At the same time I ordered my Telegraphist who was standing by, to make Double Item by W/T [wireless telephone] on 500 kc/s and also 90° to port in P/L [plain language] and to make executive by W/T as short blasts were sounded. In the urgency of the moment it seemed that in conjunction with the blasts this was the quickest way of ensuring that all ships would turn in the direction and no time could be allowed for acknowledgement. First turn to port was executed at 1920z and second long blast sounded as ships came round. At 1923z the second turn was made to port. I simultaneously ordered the course of the convoy made on W/T in plain language and also stop engines.”[20]

The situation the convoy now found itself in was one of considerable peril and some kind of disaster was almost certain to ensue. There were seventy-nine ships in the main part of the convoy in columns 1000 yards apart and probably no more than 600 yards from the ship ahead, likely invisible but for the fog buoys in the dense fog of a late afternoon (local time), and all travelling at nearly 10 knots (11 mph). The time to travel 600 yards at that speed is about 100 seconds. A convoy emergency (single item) turn of 40° or 45° to either starboard or port was a standard procedure when encountered by U-boats and was evidently practiced on occasion and announced by signal flags, horn, W/T, radio, and flares if necessary. It was still a hazardous maneuver even in the best of conditions with ships of different displacements and turning abilities and required close attention. A turn of 45° was normal in skirting dangers but in this case with an evident barrier of ice directly ahead and along the whole front of the convoy then the choice was either to come to a complete stop or attempt a 90° turn. At 9.5 kt with only a few minutes remaining before colliding with the bergs the safer option was to execute a double emergency to port, i.e. a 90° turn done in two stages of 45° with a three minute interval in between to allow the ships turning simultaneously together but of various turning abilities trying to maintain some sort of order before executing the next turn at the blast of the Commodore’s horn. From their reports it is clear that both S.O.E. Thompson and Commodore White knew what this was going to entail[21].

In clear weather the traditional mode of alerting the ships in the convoy was by flag signals from the Commodore’s ship, the turn to be executed (made executive) at the lowering of the flag hoist. This was impracticable in the foggy weather at the time so the Commodore’s had to resort to W/T (Morse code on Wireless Telegraph) and plain language on Radio Telephone first alerting the ships by a 15 second blast on the horn and the turn to be executed at the sound of the short blasts.

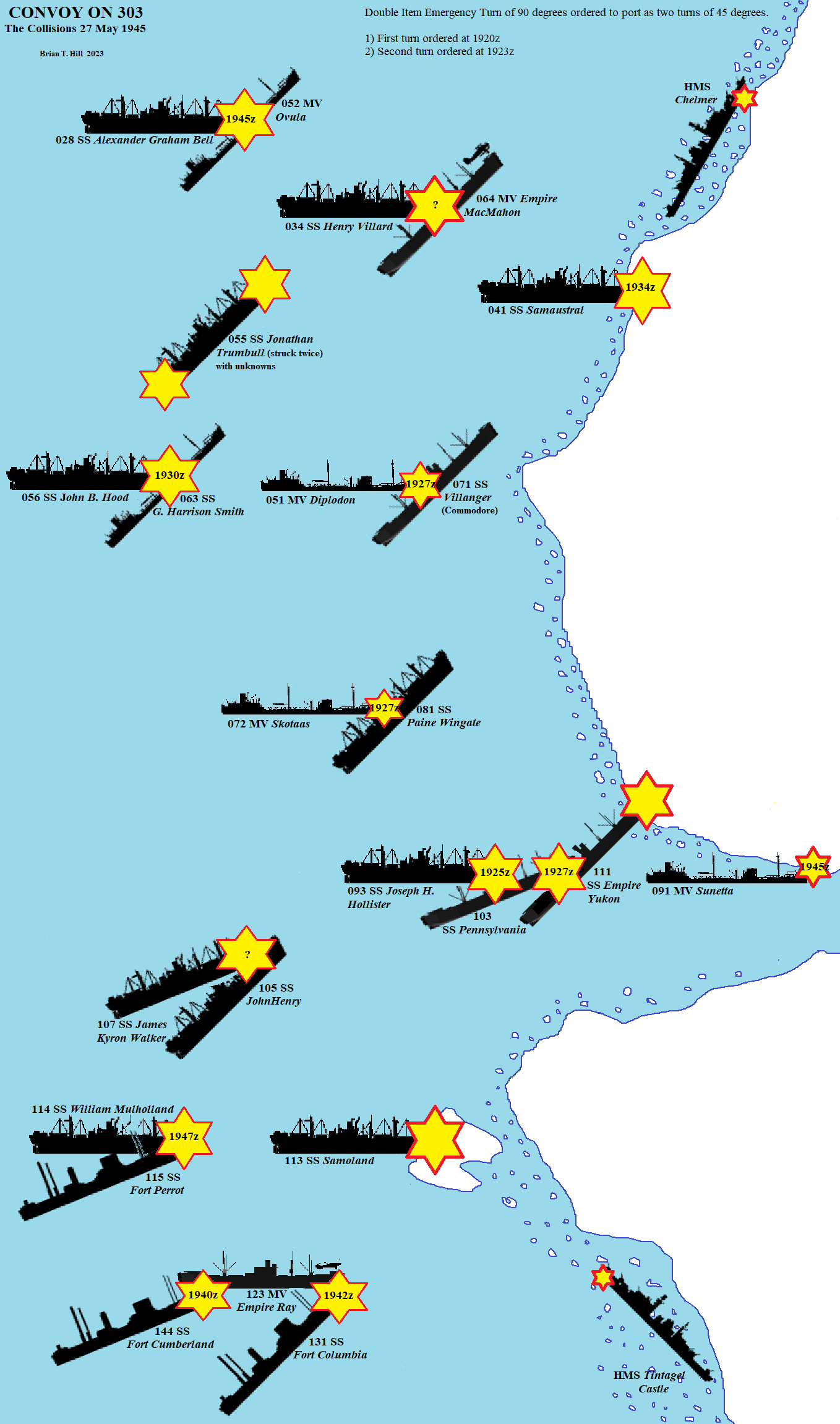

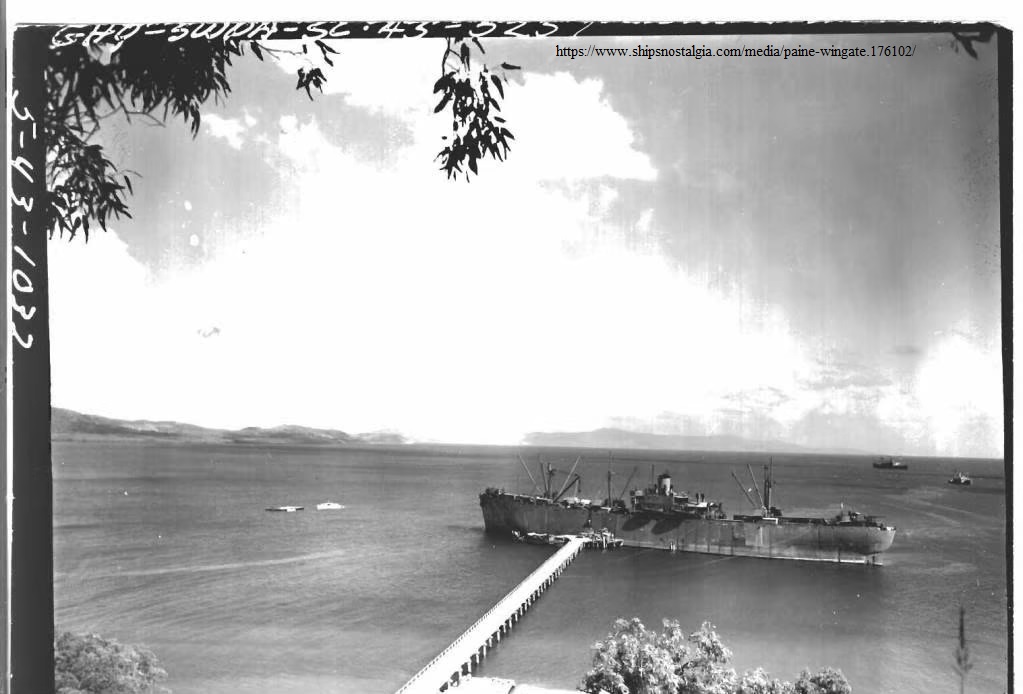

Apart from dense fog it also began raining hard which would also help mask sound and further hinder visibility. The horns on many ships are largely directional mounted on the fore side of the funnel or occasionally the mast but pointing forward with the intent of warning oncoming ships rather than those abreast or astern. The first collisions to occur were all with ships in forward positions being struck by vessels either abreast or behind on the starboard side suggesting that as the lead ships made the turn to port others did not, or at least not as quickly. At 1925z (also noted as 1927z) the Villanger (position 71) was struck violently stem on by the Diplodan (54) abreast of No. 5 cargo hold which was holed and filled with water. Also at 1927z Paine Wingate (81) was in collision with what is thought to be Skotaas (72), and the Joseph H. Hollister (93) collided with what is believed to be Pennsylvania (103). At 1930z the John B. Hood (56) was in collision with possibly the G. Harrison Smith (63).

The next collisions occurred as four ships encountered the ice. Three of those vessels were at the head of their columns and so would be expected to meet any obstacle first but the Samaustral (41) is reported as coming into collision at 1934z, some minutes after the orders to make the two turns to port and to stop engines were made suggesting that they also did not hear the commands. The Samaustral sustained damage described as not serious, the Empire Yukon (111) damaged the port bow and quarter but was not making any water, and the Samoland (113) and the Sunetta (91) touched an iceberg at 1945z losing an anchor. In fact, by her own admission the latter stated she was on the old course, presumably not hearing the signal to turn, and found herself between icebergs.

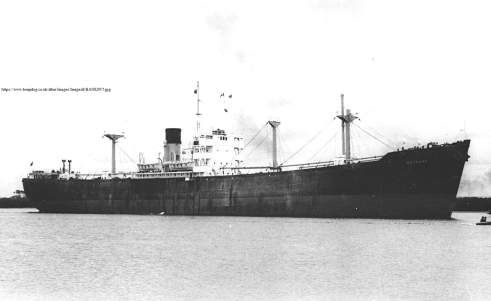

In the poor visibility of rain and fog, with some ships coming to a standstill and others not, the mayhem was not yet over. At 1940z the Empire Ray (123) was in collision with Fort Cumberland (144) then gone on to collide with the Fort Columbia (131) at 1942z. At 1945z Alexander G. Bell (28) collided with Ovula (52) which had completed the 90° turn and was on a course of 143° receiving slight damage. At 1947z the Fort Perrot (145) collided with William Mulholland (114) which received a hole in its side. At unknown times James Kyron Walker (107) collided with John Henry (105), Empire MacMahon (64) with an unknown vessel though elsewhere it is stated with Henry Villard (34), and it is thought the Jonathan Turnbull (55) was also involved in two collisions. In fog and rain it is easy to imagine the pandemonium and general confusion which is evidenced in a sample of the signals:

081 [Paine Wingate]: “collision port side amidships am stopping to determine damage will then continue at 6 knots.”

041 [Samaustral]: “hit iceberg”

015 [John Henry]: “rammed fore peak filling up am stopped pse advise”

107 [James Kyron Walker]: “collided with 105 [John Henry] am proceeding at 6 knots.”

114 [William Mulholland]: “145 [Fort Perrot] collided with me hit stbd side number five hatch unable to continue advise.”

111 [Empire Yukon]: “large iceberg alongside.”

054 [Diplodon] “steam whistle broken down am using emergency horn.”

091 [Sunetta]: “pse notice we followed old course and between icebergs.”

015 [Herman Melville][22]: is convoy supposed to be stopped”

047 [Duncan L Clinch]: “Are we still stopped”

051 [Walt Whitman]: “Who is now in charge of convoy”

The Hadley F. Brown (142) suffered some kind of damage but it is not exactly clear to what extent. Early in the morning of the 26th she had reported that she had ten feet of water in No. 1 hold. The master was concerned that the bulkhead would not stand up to the ship’s movements and asked to go to St. John’s. This request was denied once the ice report came in and it was decided that the ship remain with the convoy until such time as the other ships bound for Newfoundland were detached. The S.O.E. seemed to think that the water came from an internal rather than an external source, however, in the list of ships in the Convoy Commodore’s report her name is appended in handwriting as having being in collision and remaining with the convoy until it reached New York just after midnight on June 3. Her name is not actually listed with the ships which were in collision so it is not clear if she was or was not. In addition it appears that two of the escorts were damaged by ice. In his narrative the S.O.E. makes no mention of his own escort ships being in collision yet in Section 7 of his report, labelled “Material”, he lists the Tintagel Castle’s ASDIC’s dome as being punctured by ice and his own Chelmer with No.1 and No.4 fuel tanks leaking. With Chelmer in the van and the first to reach the ice it is possible she could have sustained damaged at that time. The Tintagel Castle was supposedly stationed on the starboard side of the convoy and as it made its emergency turn to port away from the ice that would have put the Tintagel Castle closest to it.

So, of the seventy-nine merchant ships in the convoy at this time, four hit the ice with at least three damaged, and twenty-one ships hit each other for a total of twenty-four, perhaps twenty-five casualties. Add to that the two escorts and we have six ships in contact with ice suffering some degree of damage not just one or two as has been often reported for a total of twenty-seven ships being in collision. Although not involved in the mayhem there was also the damage to the ASDIC dome of H.M.C.S. Sussexvale which was undoubtedly due to contact with ice. Although several ships were holed, five fairly seriously and judged to require docking, none were apparently at risk and remarkably there is no report of personnel injury. Of the ships that came into contact with ice they all came through relatively unscathed leading the IIP in their annual bulletin[23] to remark that they likely hit growlers rather than the massive berg but although the damage to the Sunetta was light we now know that she lost an anchor meaning that she had to ‘touch’ a sizeable near vertical face in order to remove it. Considering that the convoy may have been upwards of five miles across and that the one ice island was ¾ mile long it presented a formidable obstacle to avoid entirely. The diagram in Figure 4 shows which ships ran into which.

Reforming

At 1937z[24] tugs were ordered from St. John’s which seems remarkably prompt as collisions were still taking place. As both the Commodore in the Villanger (071), and the Vice Commodore in the Empire Yukon (111) were in disabled ships, the Commodore asked the master of the Empire Stuart (141) to take over his duties as Commodore at 1941z. By 2200z the convoy was moving slowly back due east away from the ice and the master of the Villanger undertook what repairs he could. The bulkheads had been shored up and the after ballast tanks pumped out and although the ship was in no danger of sinking it could still no longer keep up with the convoy. The Commodore then requested the S.O.E. to have one of the escorts close on the Villanger. In the poor visibility it was found by HMS Tintagel Castle at about 2230z and the decision was made to transfer the Commodore and his staff and all their baggage to the Tintagel Castle, a process maybe taking a couple of hours with the ship’s small boat[25]. However, it appears that around this time, the Commodore and perhaps the S.O.E. may have visited the Empire Stuart, as Midshipman Fields recalls that while being hove to near the icefield the naval ratings (the gunnery team) lined up to welcome the party aboard. We do not know why the Commodore did not resume his duties there but since transferring all his staff and baggage evidently was going to take some time, it is conjectured that this visit was a quick briefing to aid the master of the Empire Stuart in his newly acquired duties of restoring order to the convoy as quickly as possible.

The main part of the convoy now at about 43°08´N 49°15´W and under the escort of the Inman then turned due south steering a diversion around any further contact with ice and hoping to clear the fog. HM ships Poppy and Lotus meanwhile herded in the stragglers while the Chelmer and Tintagel Castle remained in the vicinity of the icebergs looking for seriously damaged ships. Given the vicinity in which they were then patrolling it is possible that this was the time in which they were damaged.

As the straggled out convoy limped slowly southwards initially at about 4 knots, the Admiral in Halifax, acting on some estimate that he had received that the fog limit extended only as far as 42°40ʹN sent a number of messages early in the morning of the 28th directing that once the convoy had reformed it should aim for 42°30ʹN 50°W and then on to a new WESTOMP at 42°30ʹW 53°01ʹW for 1800z. The C. in C. C.N.A. had evidently underestimated the seriousness of the situation despite earlier signals from the S.O.E. outlining the extent of the collisions, the damage and the current speed of the convoy. The speed required to meet the new WESTOMP was based on the service speed of over 9 kt. With the convoy straggling over 40 miles of ocean the S.O.E. politely informed the C. in C. C.N.A. that they were yet unable to reform and were proceeding south at 6 kt in an endeavor to gain improved visibility. This southward track would now take the convoy into the intended track of eastward bound Convoy HX 358 which at their closest points would be around noon with HX 358 about 30 miles to the west. With each convoy covering several square miles of ocean and the possibility of stragglers, the C. in C. C.N.A. not wanting any more debacles on his watch, warned both Convoys ON 303 and HX 358 to keep a sharp look-out for one another, further warning HX 358 to keep well clear of ON 303 by steering 10 miles to the southward of its intended route until crossing 48°W[26]. A short while later, with the danger of more collisions now more a threat than U-boats, he sent a further message which would subsequently be sent to all convoys; “You may burn navigation light from tonight”. One wonders what difference it might have made if it had been sent twenty-four hours earlier.

At 1000z on the 28th the Commodore and staff had transferred to HMS Chelmer and at 1200z the position was 41°38´N 49°17´W, ninety nautical miles since turning south. A few minutes before noon, possibly around 1110z the cargo ship Ida Straus came closer to her namesake than probably anyone could have ever imagined. In latitude 41°44´N the wreck of the Titanic lay just thirty-seven nautical miles to the west, just over three hours steaming. Ida’s body was never recovered, no one knows where it lay but it would be nice to think that it lay not very far away at all.

The convoy continued south with HMS Inman searching ahead for an improvement in the weather while the Empire Stuart consolidated the main body of the convoy. Following instructions to release the Dutch tanker Ovula before dark she was detached at 1500z in about 41°16´N 49°08´W[27] for Port Arthur, Texas. At last they cleared the fog and in 41°01´N 49°03’W at 1717z with 64 ships in some semblance of order the convoy made the turn to 300° for the latest WESTOMP proceeding at 6 knots. Poppy and Lotus remained at the turning point acting as goalkeepers to shepherd the remaining ships while the Chelmer and Tintagel Castle brought up the rear. By 2007z 68 ships had reformed and a little while later at about 2100 Commodore White and his staff were transferred to SS Samthar and resumed command of the convoy.

In reforming the convoy assistance had also been provided by two other ships in the area. The Ice Patrol U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Mojave which was on duty in the area had been ordered to render assistance shortly after the collisions took place was detached at 2300z to resume her ice patrol now that the convoy was safely on its way with 70 ships back in station and proceeding at 7.5 knots. Another U.S. ship whose name is not known reported that it had three other ships still in the fog and it was further requested to assist them to the rendezvous which was now requested at 42°08´N 52°13´W for 1400z next day, the 29th.

The Canadian Western 8th Escort Group (W8EG) had sailed from St. John’s at 1000z on the 27th for the WESTOMP at 43°02ʹN 53°01ʹW, then diverted to the new WESTOMP, and subsequently knowing that the convoy could not reach there for the time given, made directly for the convoy. The Canadian escorts, the corvettes HMC Ships Kenogami and Forrest Hill accompanied by the minesweepers HMCS New Liskeard and Drummondville joined with the convoy a little before midnight on the 28th and the B.1 escorts Inman, Poppy and Lotus were released for St. John’s shortly after. The S.O.E. in the Chelmer waited till first light before turning over command to the Kenogami and then he and the Tintagel Castle departed also for St. John’s. The convoy had now re-assembled to seventy-two ships and the whereabouts of all but two of those not in company were known and were assumed to be proceeding independently ahead.

As requested, three tugs, the Tenacity, Chippawa, and Comanche, had sailed from Newfoundland for the scene of the collisions. HM Rescue Tug Tenacity was based at St. John’s and the USS fleet tug Chippawa was stationed at Argentia and both were underway within a couple of hours of the S.O.E.’s request with the minesweeper HMCS Medicine Hat escorting the Tenacity. The Comanche was an U.S. Coast Guard Cutter similar to the Mojave and sailed later that evening also from Argentia. It now looked as if all the damaged ships in the convoy were capable of proceeding without assistance but arrangements were still made to have the tugs rendezvous with the vessels in case needed. It is not known when the Chippawa arrived but the Comanche was expected at 0900z and the Tenacity with the Medicine Hat joined at approximately 1100z on the 29th. The Commodore broadcast to his ships asking to be notified of any requiring assistance and since no replies were received the support vessels were released a few hours later after reaching the rendezvous point about 1400z; the Tenacity and Medicine Hat back to St. John’s, the Comanche back to Argentia and the Chippawa to patrol for ice south of the Banks.

After passing the rendezvous point, the convoy was able to pick up speed and resume much as planned although a few ships had to proceed independently. At 1400z the Drummondville detached with four ships for St. John’s (James B. Hickok, Fort Perrot, Empire Stuart and Fort Cumberland). The Fort Columbia originally intended for Corner Brook now proceeded independently for damage survey in Halifax. The ten ships (Empire Yukon, Samsmola, Lochmonar, Empire Ray, Mount Kylene, Axel Johnson, Fort Prudhomme, Trevider, Coulgorm and Algenib) bound for the Gulf of St. Lawrence detached at 2000z and the convoy now took on a more westerly course of 277° towards Halifax.

With the Newfoundland bound ships now released, on the morning of May 30 the convoy regrouped with the Halifax bound ships in the starboard wing and the tankers in the centre columns. By noon the average speed over the last twenty-four hours had picked up to 9.6 kts and at 1930z eight of the faster twelve knot ships were detached for Boston and New York. At 0600z on May 31 with Halifax about 140 nm to the west-northwest the five Halifax ships were detached and these included the MAC ships, Empire MacCabe and Empire MacMahon and the Rescue Ship Bury. By noon the distance made good by the convoy was only 41 nm in the six hours since detaching the Halifax ships with an average speed of 6.8 kt but no doubt considerable time had been spent in the redistribution of the ships within the convoy. Thereafter, an average speed of 9.2 kt was maintained until 1700z when the remaining Boston ships were detached. Speeds of nine to ten knots were maintained until the remaining ships of the convoy reached New York with the lead ships arriving at 0129z on 3 June.

Discussion

There are a number of small inconsistencies between the S.O.E. Thompson’s and Commodore White’s reports. This would be understandable in any situation and more so in the confusion of collisions of a convoy of over 80 ships in fog, rain, ice and impending darkness. The S.O.E.’s report was signed May 30, the day the Ocean Escort arrived St. John’s. It is not evident when the Commodore wrote his but his forwarded report was signed by the Canadian Joint Staff on 4 July. The Commodore lists four ships, the Empire Yukon, Samaustral, Samoland, and Sunetta, as having struck or “touched” ice sustaining “more or less damage full extent not known”. Based on reports received the S.O.E. lists twenty ships as having been in collision with only one, the Samaustral, as having hit ice but with no serious damage. In his Section 7 he also mentions the ice damage to ASDIC dome of Tintagel Castle and that the No. 1 and 4 fuel tanks of the Chelmer were leaking which could also indicate ice damage. It is not known when the damage to the two escorts occurred but it would appear at any rate that the four convoy ships encountered ice more or less together with minimal damage and that the two escorts hit ice either at around the same time or perhaps as equally likely when rounding up the last of the ships well into the late evening of May 27 when close to the ice.

As well as striking ice, the Commodore also lists the Empire Yukon as being in collision with the Pennsylvania at approximately 127 GMT[sic=1927z?]. The turn of events is not clear but if the time is correct then perhaps she was struck by the Pennsylvania before going into the ice as her 2003z message states that a large berg was alongside. This might indicate that she was already in the turn before being struck by the Pennsylvania which was either not turning or at least not as quickly. The damage to the Empire Yukon was to the port side and the way it is described in the reports suggests it is as ice damage. The Johnathan Turnbull is noted as having been in two collisions. Excluding the Empire Yukon the Commodore lists twenty ships having been in collision with each other. Excluding the Samaustral and the Empire Yukon the SOE lists eighteen ships in collision but was not sure whether one is the John Henry or the Patrick Mahoney. The ships he does not mention that are in the Commodore’s report are the Henry Villard and the Fort Cumberland. The former was in collision with the Empire MacMahon with unknown but not serious damage, and the latter was in collision with Empire Ray according to the Commodore’s report but there is no description of any damage to the Fort Cumberland. Further, there is the Hadley F. Brown which is not mentioned in the Commodore’s list of more-or-less damaged ships but has a penciled “in collision” beside its name in the list of convoy ships although we know her troubles began the day before the collisions[28]. Thus it seems, there were twenty-two ships in collision with each other including the Empire Yukon which is also one of the four ships that hit the icebergs. Five ships, the Diplodan, John Henry, Paine Wingate, Skotaas and Villanger, were holed or damaged to such an extent that docking would be required for repairs.

The Commodore concluded his report by stating that under the extreme foggy conditions at the time an immediate turn of at least ninety degrees was the only option available but that under those conditions collisions must be inevitable. Damage was slight, however, and although the list of ships damaged was considerable, no ships were sunk and no lives were lost. Unless the turn had been made a major disaster would have occurred with ships piling up in succession upon the ice and with hundreds of troops on board would probably have incurred extensive loss of life. He expressed appreciation of the ability of the Rear Commodore in Empire Stuart for taking over at short notice and keeping the convoy together. Considering the necessarily inadequate time for signals to get round the convoy of eighty ships and that sound signals were hindered by the fog and rain he insists that as a whole the convoy deserves credit for exercising the maneuver as successfully as it did with as little serious damage.

The S.O.E.’s concluding remarks also greatly credits the master of the Empire Stuart on taking charge after the Commodore and Vice Commodore’s ships had been disabled stating, “The manner in which he controlled the scattered ships, led them out of the danger area and formed up the convoy was a fine example of skill and leadership.” Alas, in neither of the reports is the name of this fine and capable officer mentioned. However, subsequent research has revealed his name as Captain Norman Jameson and that he was awarded the O.B.E. just a few months later in January 1946[29].

The S.O.E.’s report was reviewed and commented on by Newfoundland Force Acting Captain E.A. Gibbs, RCN, DSO and 3 bars, Captain (Destroyers) Newfoundland in a statement to Commodore C.R.H. Taylor, RCN, Flag Officer, Newfoundland dated 11 June 1945. He quickly points out that radar detection by the Chelmer of a large iceberg at a range of only 6000 yards is a further indication of the uncertainty of ice detection by radar. At this period of time radar development was very much in its infancy and its transparency to ice was obviously already apparent. The only hint of censure in his statement was that the S.O.E. might have previously stationed one of his escorts well ahead on an ice-warning screen[30] but smooths it over when he goes on to say that the ice encountered was far to the south and west of any reported in the most recent Ice Bulletin, a copy of which he attaches. In any case, he continues, the convoy would still have to be turned or stopped and lacking efficient communication collisions would still have occurred. Although Gibbs admits that the method of affecting the “Double Item” turn was not stated by the S.O. he was personally informed by him that sound signaling was used. Due to the long time in the fog the convoy may have been considerably strung out in which case many of the ships may have not heard the signal and that would account for the many collisions which occurred. However, this is in contradiction to the Commodore’s report in which he states that on the forenoon of the May 27, the day of the accidents, the convoy was able to regroup and close up. Had the turn been ordered and executed by W/T on 500 K/c’s [sic] Gibbs continues, would be the only safe way of avoiding catastrophe, but that the catastrophe did occur during one of the single operator periods [when there was no wireless operator on duty], presumably preventing the use of W/T. However, as we know the CC did try and communicate by both sound and wireless. Captain (D) Gibbs concludes his remarks by praising the unnamed Master of the Empire Stuart and suggesting that letters of appreciation be written both to the master and the ship’s owners.

In his submission to Vice-Admiral George C. Jones, The Commander in Chief, Canadian Northwest Atlantic, Halifax, Flag Officer Taylor writes as of 15 June 1946:

“2. The experience of O.N. 303 again shows the difficulty of avoiding ice bergs at this season unless an extreme southerly route is taken. It is considered the Senior Officers B.1’s action, this being his first experience of ice, was sound, in that he considered the safety of the convoy was best assured by a drastic alteration of course to avoid ice. That this action should have resulted is [sic] so many collisions was probably due to the fact Commander R. Thomson, R.N. did not appreciate:

(A) Convoy was probably scattered due to steaming in thick fog for four days;

(B) Being a fortnight after cessation of hostilities the convoy was not so alert as could be normally expected.

3. The Master of the “Empire Stuart” is to be commended for his coolness in this emergency.”

As has already been noted the convoy was, as far as we know, tightened up but there could be some element of truth in (B) as the ships were slow to wake up after the commodore’s first blast on the horn. The Flag Officer’s opening sentence highlights the threat of icebergs perhaps even with a slight hint of censure for not taking a more southerly route (remembering his reminder about the ice warning to the convoy on May 26 when he passed along the information about the new WESTOMP). The Admiralty was responsible for convoy routing across the north-Atlantic but from longitude 47°W to the U.S. Eastern Sea Frontier boundary it became the responsibility of the C. in C. C.N.A.

The priority in routing was the safe transit of the convoy through U-boat infested waters but ice was also a concern. The authors know of at least a dozen incidents prior to Convoy ON 303 in which both merchant and naval vessels collided with icebergs, two of them involving fatalities. Due to wartime restrictions on publication no doubt there were several more collisions and the authors’ list does not include those damaged by sea ice. The most serious accident was the loss of the tanker Svend Foyn, converted from a whaling factory ship, which struck an iceberg and sank with the loss of forty-three lives on 19 March 1943. When The International Ice Patrol resumed service after the war the wartime sea ice and iceberg observations of the U.S. Coast Guard were published in later IIP annual bulletins together with their plotted positions in a monthly ice chart. The charts showing the iceberg distributions for March and April 1945 are redrawn here in Figures 5 and 6 and when compared with the chart from May (Figure 7) the progression of icebergs during the early part of the season is clearly seen. The waypoints, JO to JP, of the intended route of the convoy are shown in each of the figures as a visual reference and it is evident that the original routing made no attempt to avoid the known icebergs. Only the icebergs as known by the Admiralty up to the point of the convoy departure on May 17th are shown, coincidentally at about which time ice observations were temporarily suspended due to inclement weather.

As noted previously, a ship in a previous convoy had already been damaged by an iceberg. The Dutch freighter Aalsum of Convoy ON 301, out of the UK and likely on a similar track as ON 303 and bound for Sydney, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, was reported in collision in 45°N 48°W on May 17 the same day Convoy ON 303 was gathering. With Convoy ON 303 heading for the Grand Banks with a precious cargo of nearly 4,000 troops homeward bound troops distributed throughout twelve ships[31], the fact that a convoy ship had just recently been damaged by ice must have been key in the decision to divert the convoy to the southward. By the time ice observations resumed and the ice report of May 26 was issued the convoy was already heading southwestwards to point JT to avoid the ice.

In his account, Acting Temporary Sub Lieutenant F.N. Goodwin, RNR who was aboard HMS Tintagel at this time, refers to a Public Records Office document by W.A. Stephens, the Director of the Admiralty Trade Division, the department responsible for convoy planning and routing and of the escorts in the Western Approaches. On 24 June 1945, explaining with the aid of a chart, Stephens showed how the convoy had already been diverted to the southward to pass about 120 miles south of a known area of ice north of 44°30´N on the eastern edge of the Grand Banks[32]. However, Stephens goes on to state that the convoy encountered ice just some eighty miles south of the area of known ice. It is not clear what points Stephens was using for his distance comparisons and presumably he was referring to diverting the convoy through the new J position, JT, in 43°N 49°W. However, eighty nautical miles south of 44°30ʹN is in 43°10ʹN where the collisions occurred so what is implied is that if the convoy had stuck to the original 120 mile diversion it would have cleared the ice. See Figure 8.

Stephens then went on to explain that owing to escort considerations convoys have to be routed as near to Halifax and St. John’s as possible for ships leaving and joining and that in the ice season the C. in C. C.N.A. had to keep these convoys as far to the northward as appeared safe and that the situation shown in his chart did not suggest any failure on his part to route the convoy reasonably clear of known dangers. So, we appear to have clear evidence that the C. in C. C.N.A. altered the Admiralty’s safe diversion around the ice for a risky short cut through it as soon as the convoy crossed 47W, or shortly after, when he had the authority to change it putting the lives of thousands of sailors and troops at risk. There is no obvious reason why he should have done so. There were no other inbound or outbound convoys in the immediate area and even eastbound HX 358 was still thirty miles away even after the flight south after the collisions. However, it is worth pointing out that at any one time there were about 20 convoys at sea in these North Atlantic runs, about a thousand ships, each with its escorts, and it was important to have the WESTOMP as close to St. John’s and Halifax as possible so that the escorts could refuel and revictual in readiness for the next returning convoy. In fact, it looks like the decision to short-cut through the edge of the Banks was made by the time the Sussexvale detached at 2100z on the 26th. As noted previously, the distance from the 2100z position to WESTOMP via JT was 410 nm requiring a speed of 10.25 kt to get there for 1300z on the 28th. By turning to a more westerly course at 1200z on the 27th reduced the distance to the WESTOMP sufficiently that by maintaining a speed of 10 kt the convoy could reach it by the set time. If saving in time or fuel was part of the reason for the shortcutting across the Tail of the Grand Banks then the irony was that at 10 kt the saving was only a little over an hour (Fig. 8).

The last course change before the collisions remains a bit of a puzzle. From noon on May 26 to noon on May 27 the course was 229° which was on the track for position JT. However, the May 27th 1500z position was almost due west at 261° as if the convoy was now making straight for the WESTOMP (260°). Had the convoy maintained this course there was a reasonable chance the convoy could have crossed without harm as, as can be seen in Figure 8 the bergs were reasonably scattered. But by 1500z the convoy was on a course of approximately 233° at a speed of 9.5 to 10 kt which was held for four hours until Commander Thomson in the Chelmer detected the large iceberg. If the convoy happened upon some early ice and made some diversionary tactics on their own there is nothing in the reports or marine signals to suggest anything. There is one signal, however, from Commander Thomson sent at 1727z to the S.O. W8EG and HMCS Drummondville giving the 1500z position, course and speed and informing him of the ten feet of water in the Hadley F. Brown’s No.1 hold and the master’s request to be detached to St. John’s. So it does confirm that the current course was known by all. The reason for the change to this course remains unknown but a logical assumption is that by 1500z the convoy had already detected the presence of ice and was being pushed southwestwards to avoid it. Unfortunately, this was a path into a cluster of icebergs at their thickest (Fig.8).

Vice-Admiral George C. Jones was new to his job as Commander in Chief of the Canadian North-western Atlantic having just replaced his long term bitter rival and the original C. in C. C.N.A. Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray on 12 May after the debacle of the Halifax riots during which over-zealous sailors had celebrated the victory in Europe by pillaging and ransacking the streets of the city. Murray had seen long service with the navy since prior to the first World War with particular interest in convoy systems and risen to commanding the Newfoundland Escort Force as a Rear Admiral in 1941 and Commanding Officer Atlantic Coast in 1942. He became C. in C. C.N.A. at its creation the following year and was the only Canadian to command an allied operational theatre during the war. Jones had equally a long a service as Murray but had gradually outranked him and was currently Chief of Naval Staff in Ottawa. While he had had several significant commands under his belt his prowess was as a staff officer and bureaucrat rather than with practical skills and was once noted as having taken an hour and a quarter to park his ship[33]. As if to settle long standing scores he now chose to replace Murray personally. Their rivalry was well known within the service; they did not communicate with one another[34] and care was taken to ensure that both did not attend the same functions together. While this rivalry did not significantly impact the service it divided loyalties with each admiral having his own faithful camp of officers following from posting to posting[35].

Now, having vanquished his rival, Jones assumed all his roles and responsibilities as the new C. in C. C.N.A. He had been himself the Commanding Officer Atlantic Coast in the early part of the war but principally a staff officer he may not yet have been comfortable in his new role in charge of an operational command. By all accounts Murray was a hugely popular person while Jones was not and could be difficult to approach. So, in the turmoil in the aftermath of the riots with some staff perhaps holding grudges it is possible he may not have sought or been given the advice he needed to make sound decisions and, as an example, his signal to reform the convoy and head for a new WESTOMP shortly after the collisions indicates he was not fully in tune with the situation.

“Assume these reports will be forwarded to Admiralty. The routing blokes there never took ice and fog off the Grand Banks very seriously”[36] wrote someone on a Naval Service Minute Sheet to which someone else wrote ‘Yes”. The memo is dated 14 June 1945 and although signed with largely illegible initials we think them to be JD which would correspond to Lieutenant-Commander Frederick John Day who served almost the whole duration of the war in Halifax, latterly as Staff Officer Convoys to the Commander-in Chief Canadian North-west Atlantic. While he appears to have been transferred by the early part of 1945 he, nevertheless, sat on the Committees of Investigation, so perhaps in that capacity still had a voice. “These reports” we assume to mean those written by Commodore White and Commander Thompson as well as the remarks written by Thompson’s superiors. Going by the reports alone there is little to suggest that anyone other than the Admiralty was responsible for routing the convoy through the ice but as we have seen they clearly had intentions of diverting around the ice and that JD’s own Commander-in-Chief held the responsibility for the final routing.

It is interesting to note that Convoy ON 304 following on the heels of ON 303 and on a similar track to the Grand Banks was diverted on the evening of May 28 to a new point at 42°10ʹN 49°00ʹW, fifty nautical miles further south that ON 303’s JT position. The order to divert also came with the warning that ice may be encountered between 46°W and 51°W and to take necessary precautions. The convoy stuck to the route and proceeded without incident.

Of some additional interest is the description by Sir Robert Atkinson, captain of HMS Tintagel Castle, in a taped interview for the Imperial War Museum[37]. This was recorded in 2003, hence the captain was trying to recall events almost sixty years previously so it is understandable if some details are obscured with time. There are several inconsistencies with the accounts we have. Some are relatively minor and the kinds of thing that would be fogged by time such as there were thirty-eight ships in the convoy instead of eighty-three, and that it was in the month of April instead of May. But more importantly he claims that he had the S.O.E. onboard[38], that they picked up the radar echoes of the iceberg initially believing that it might be an U-Boat, that they had to wake up the Convoy Commodore using every means available such as horns and star shells, and that they were so close to the iceberg they could hear the waves breaking against the sides of the berg. He thus creates the impression that they were in the lead position with the S.O.E. onboard, that they were the first to detect the iceberg and that they had to wake up the Commodore somehow to get a response. This account differs substantially from the reports which state the Tintagel Castle was on the starboard beam of the convoy and there is no mention of the S.O.E. ever having been aboard her. The Convoy Commodore did transfer to her but only after the emergency turn and the resulting collisions when his own ship was damaged. There is nothing in the reports to indicate that the Commodore needed waking up, indeed he seems to have responded immediately to the S.O.E.’scall, but it does appear that the majority of the convoy itself needed waking up. While star shells are not described in the reports it is not unlikely they were used. The accidents occurred in late afternoon, by 2030 local time it was getting dark and as the convoy retreated to the east, the Chelmer and Tintagel Castle remained in the vicinity of the icebergs looking for damaged ships. No doubt star shells were used at that time and Captain Atkinson’s description of being close to the icebergs is very detailed and vivid and likely refers to this time.

In his book, F.N. Goodwin in the Tintagel Castle, does not have much to add personally, relying mainly on the convoy reports for his description, but he does go on to say that even after the collisions while looking for stragglers they had a very near miss with an unknown ship and shortly after that, while heading south, they made radar contact with ice deducing that it was several miles long. Whether one berg or several close together could not be determined as it remained invisible in the fog and heavy rain although the waves could be distinctly heard lapping the base. He describes being with the skipper on the bridge at the time so this is very likely the situation that Captain Atkinson was describing in his 2003 taped interview.

The Director of Anti-U-Boat Division, C.D. Howard-Johnston, questioned the ability of detecting icebergs at longer range, and goes on to say, “…. it is suggested that it be made clear to Western Approaches at this stage the Admiralty takes a serious view of the matter, which it is expected will have been fully inquired into in the usual Service manner”[39]. In the end however, there does not appear to be any repercussion of the events and the incident itself seems to be largely forgotten except for a passing mention here and there, often with an overtone of humor in that two ships hit the iceberg and twenty other ships hit each other, and Goodwin’s short account appears to be the only one giving any kind of detail. While having twenty or so ships damaged in one incident may have deserved some sort of explanation, the war was over, no one was killed, or even injured; no ships were sunk and the damaged sustained was less than would be expected by torpedo, mine, or shell fire. Indeed, it was remarkable that damage was so light, for a convoy covering nearly eighteen square miles of ocean plowing at 9.5 kt towards bergs of up to nearly a mile long in dense fog. If decisive action had not been taken the result could have been much worse. There is little doubt that the emergency turn was poorly executed so there is probably a grain of truth to the statement that with the war over the convoy was not quite so alert as it should have been. Timing was of the essence and if ships missed the queue by horn or W/T then the result would be fiasco. One can well imagine that with the different steering and turning capabilities of the various ships such a maneuver could well be a challenge in the best of weather never mind in the visibility restrictions of fog and rain and it is evident that both the S.O.E. and the Convoy Commodore were well aware of the risk.